In many custody disputes, parents stop communicating with each other and begin to communicate through the child. What looks like a simple shortcut at first often turns into a heavy burden for the child:

“Tell your dad to drop you off at 5.”

“Remind your mom she owes me money for school supplies.”

But what looks like simple message-passing hides something deeper. Children in this position aren’t just carrying words. They’re carrying anger, frustration, and unresolved tension. And the cost is far higher than most parents realize.

This article explores what happens when children become the fulcrum of parental conflict, why the damage runs so deep, and how courts and families can intervene to protect them.

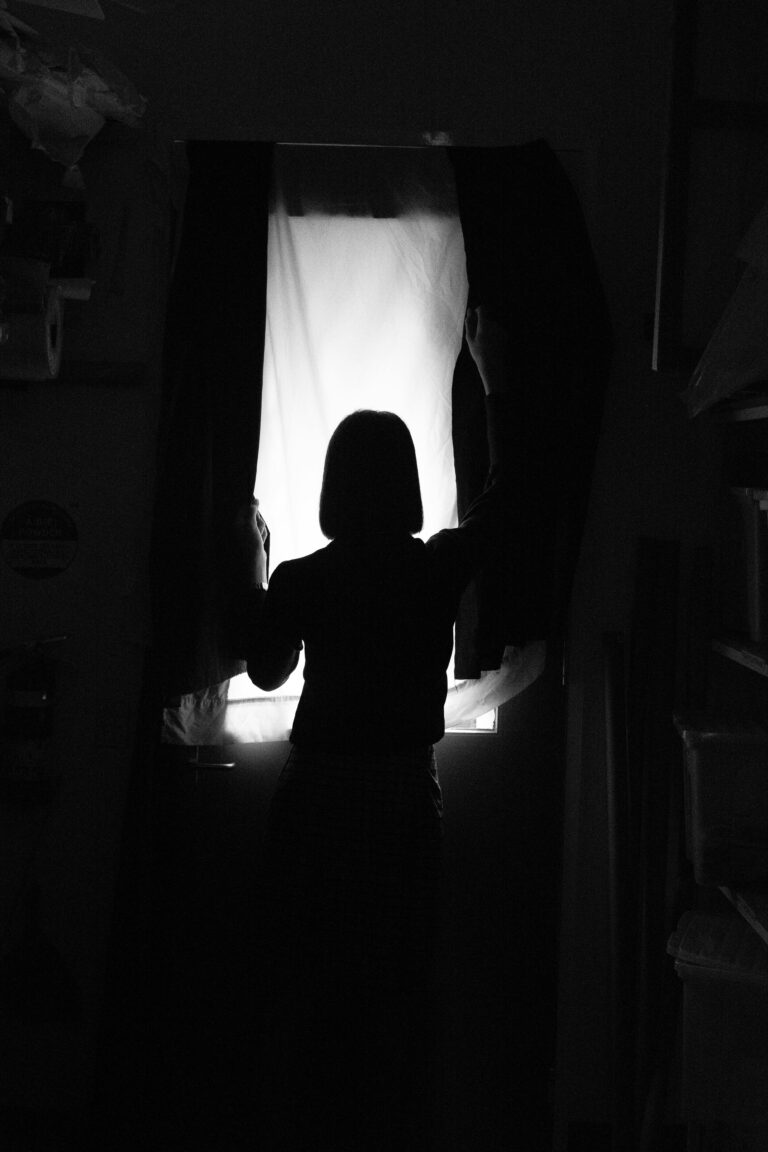

What It Feels Like for the Child

Imagine being 9 years old and walking through the door after a weekend visit. Your parent looks at you expectantly:

“So, what did your dad say about the support payment?”

You don’t want to answer. You don’t even understand the details. But suddenly, your words feel like a grenade. Whichever way you throw them, someone is going to get hurt.

That’s the heart of the problem. Children aren’t neutral messengers. They absorb the emotional charge of every message they carry, and then brace for the reaction.

Loyalty Binds: The Child Forced to Choose Sides

The messenger role puts kids in what psychologists call a loyalty bind. To deliver the message is to risk hurting one parent. To soften it is to risk betraying the other. There’s no winning.

Over time, children learn that love and acceptance feel conditional. If they please one parent, they lose favor with the other. This tug-of-war can evolve into parental triangulation, where the child becomes the emotional battleground.

Research shows that kids who are caught in the middle of interparental conflict experience a heightened sense of emotional insecurity. This, in turn, places them at greater risk for long-term difficulties, including anxiety, depressive symptoms, and problems with adjustment. They don’t just feel like bystanders. They feel responsible for holding the family peace.

Read More: Is Your Ex Using Triangulation Against You? Five Red Flags to Watch For in High-Conflict Divorce

Parentification: When Kids Become Emotional Caretakers

The danger doesn’t stop with message-carrying. Once a child is placed in this role, it’s easy for the line to blur.

Say a child delivers a message that angers one parent. Instead of walking away, the child may feel pressured to stay, calm the parent down, and listen to them vent about the other. In that moment, the child isn’t just passing along words. They’re being pulled into the role of caretaker and confidant.

This is what psychologists call parentification: when kids end up carrying adult responsibilities for their parents’ emotions. Clinical studies on parentification show that it leads to emotional distress, lower self-esteem, and difficulty asserting personal needs later in life.

Put simply: children grow up too fast. They become the emotional caretakers, conscripted into roles they never asked for.

Read More: The Parentified Child: When Triangulation Steals a Childhood

The Psychological Damage of Parental Conflict

Children who are made messengers often develop painful coping patterns:

-

- Hyper-vigilance: Always on alert for shifts in mood, watching carefully to avoid triggering anger.

-

- Anxiety and guilt: Feeling torn between parents and worrying they’ll let one down, no matter what they say.

-

- Conflict avoidance: Learning to stay silent about their own needs to keep the peace.

-

- Low self-worth: Internalizing the idea that their value comes from keeping the peace.

These patterns don’t simply fade once the custody case is over. Long-term studies suggest that exposure to chronic parental conflict in childhood leaves lasting scars, showing up years later in romantic relationships, trust, and overall well-being.

Why Parents Use Children as Messengers

Parents rarely mean to hurt their children by using them as messengers. Sometimes it’s out of convenience. Other times, anger or simply avoidance of direct conflict.

Certain personality patterns can make these behaviors more likely. Some parents use indirect communication as a relationship strategy, often without realizing the harm.

But regardless of the reason, the outcome is the same. The child ends up carrying adult tension that doesn’t belong to them.

Healthier Alternatives to Protect Children

So, what can parents do instead?

-

- Communicate directly. Even if conversations are tense, use text, email, or co-parenting apps instead of the child.

-

- Use neutral channels. Parents can use professional mediators or parenting coordinators to pass along information. In situations where conflict is especially high, the court may step in by ordering a “no-messenger” rule or requiring both parents to use a co-parenting app that keeps all communication direct, documented, and free of emotional spillover.

-

- Reassure the child. Make it clear that they are not responsible for adult issues. Their only job is to be a kid.

-

- Seek support. Therapy or parenting workshops can provide tools for healthier communication during divorce.

- Seek support. Therapy or parenting workshops can provide tools for healthier communication during divorce.

Turning the Message Around

Children shouldn’t be messengers of conflict. They should be messengers of love, reassurance, and stability. When parents commit to keeping kids out of adult disputes, they give them the freedom to grow without divided loyalty.

Because at the end of the day, no child should have to choose sides, soften words, or carry the burden of broken communication. Their only message they should ever deliver is this:

I am loved, I am safe, and I am free to just be a child.

References

-

- Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. M. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 387–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387

-

- Harold, G. T., Acquah, D., Sellers, R., & Chowdry, H. (2016). What works to enhance inter-parental relationships and improve outcomes for children? Early Intervention Foundation.

- Harold, G. T., Acquah, D., Sellers, R., & Chowdry, H. (2016). What works to enhance inter-parental relationships and improve outcomes for children? Early Intervention Foundation.

-

- Hooper, L. M., DeCoster, J., White, N., & Voltz, M. L. (2011). Characterizing the magnitude of the relation between self-reported childhood parentification and adult psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(10), 1028-1043. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20807